Overview

.jpg)

On December 29th of 2025, a series of coordinated cyber attacks took place against a number of targets connected to Polands electric grid. These targets consisted of at least 30 wind and solar farms and a combined heat and power (CHP) plant supplying heat to nearly half a million customers.

While the attack had no immedate impact on the grid, the extent of access, destructive activity, and timing (coinciding with low temperatures and snow storms) makes this a particularly worrying incident.

What particularly caught our attention is that this incident involved a TTP which we have been warning about for years, namely bricking critical OT devices as an attack amplification strategy.

Indeed it seems the threat actor behind this incident exploited a variant of CVE-2024-8036, which Midnight Blue discovered in ABB equipment a few years ago.

In this blogpost we will discuss the specific risks and technical aspects of attackers bricking embedded devices and the potential impact thereof, since there seems to be an uptick in adversary deployment of this TTP while remaining underappreciated among defenders.

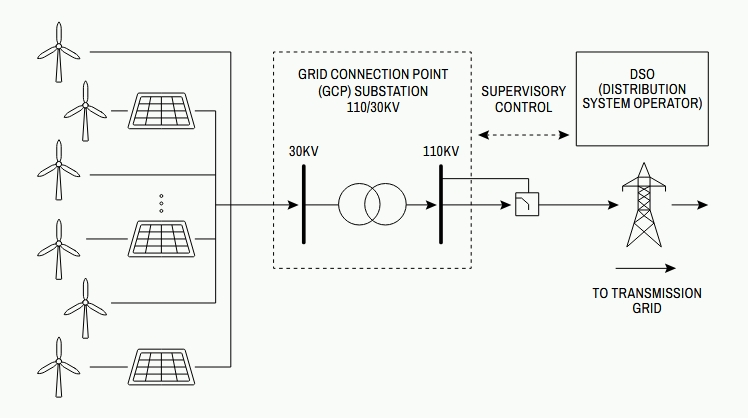

This blogpost will focus on some of the TTPs used in the attacks on the wind and solar farms. These Distributed Energy Resources (DERs) feed power into the electric grid and communicate with the regional Distribution System Operators (DSOs) through so-called Grid Connection Point (GCP) substations. At the GCP substation a Remote Terminal Unit (RTU) acts as the central telecontrol and supervision gateway interacting with the remote DSO SCADA system. Typically, the DSO SCADA system polls the RTU for measurements and status information and can send commands or setpoints to specify grid parameters, disconnect power, and regulate generation capacity.

DSO SCADA communications with the RTUs was reported as occuring via DNP3.0 or IEC-101 protocols over cellular or wired router links sitting behind FortiGate integrated firewall & VPN concentrators. Reporting also incidates DSOs in Poland typically require communications between SCADA and GCPs to occur over serial links, with IP-to-RS232/485 serial converters being present in the substations as well. It is somewhat unclear from the reporting how this works exactly (since there won't be an actual point-to-point serial cable between RTU and SCADA) but from what could be gathered it seems the RTUs either were connected via serial links to routers with built-in serial-to-IP converters or they used another Ethernet connection with IP-to-serial-to-IP conversion in between.

While this seems somewhat cumbersome, it makes sense to mandate serial interfaces only at security perimeters to limit the amount of exposed attack surface. After all, an attacker capable of talking to an IP stack across a security perimeter has the opportunity to exploit more parsing vulnerabilities or invoke more latent protocol functionality.

The RTUs in turn communicate with various devices in the substation, including protection relays which govern fault detection, isolation, and the tripping of circuit breakers.

The attacks resulted in a loss of communications between the GCPs and DSOs but such a loss of communications does not mean the DERs stop feeding power into the grid which has the potential to cause grid imbalances. For further background on the incident, we recommend the comprehensive technical report from CERT-PL, the ESET writeup on the involved wiper, and a great deep-dive series on the (potential) cyber-physical impact scenarios by Ruben Santamarta [1, 2].

During the incident, the attackers attempted to disrupt a variety of OT devices in each substation by probing them in ascending IP address order. That is, they attempted to render the devices functionally inoperable or at least unresponsive - including bricking some in such a way that they would need to be physically replaced.

Relion IEDs provide protection and control functionality within substations, such as controlling circuit breakers and switch gear and detecting fault conditions. The CERT-PL report mentions two cases of attackers connecting to IED's FTP service using default credentials in order to delete essential files in such a manner that the device was prevented from being properly restarted.

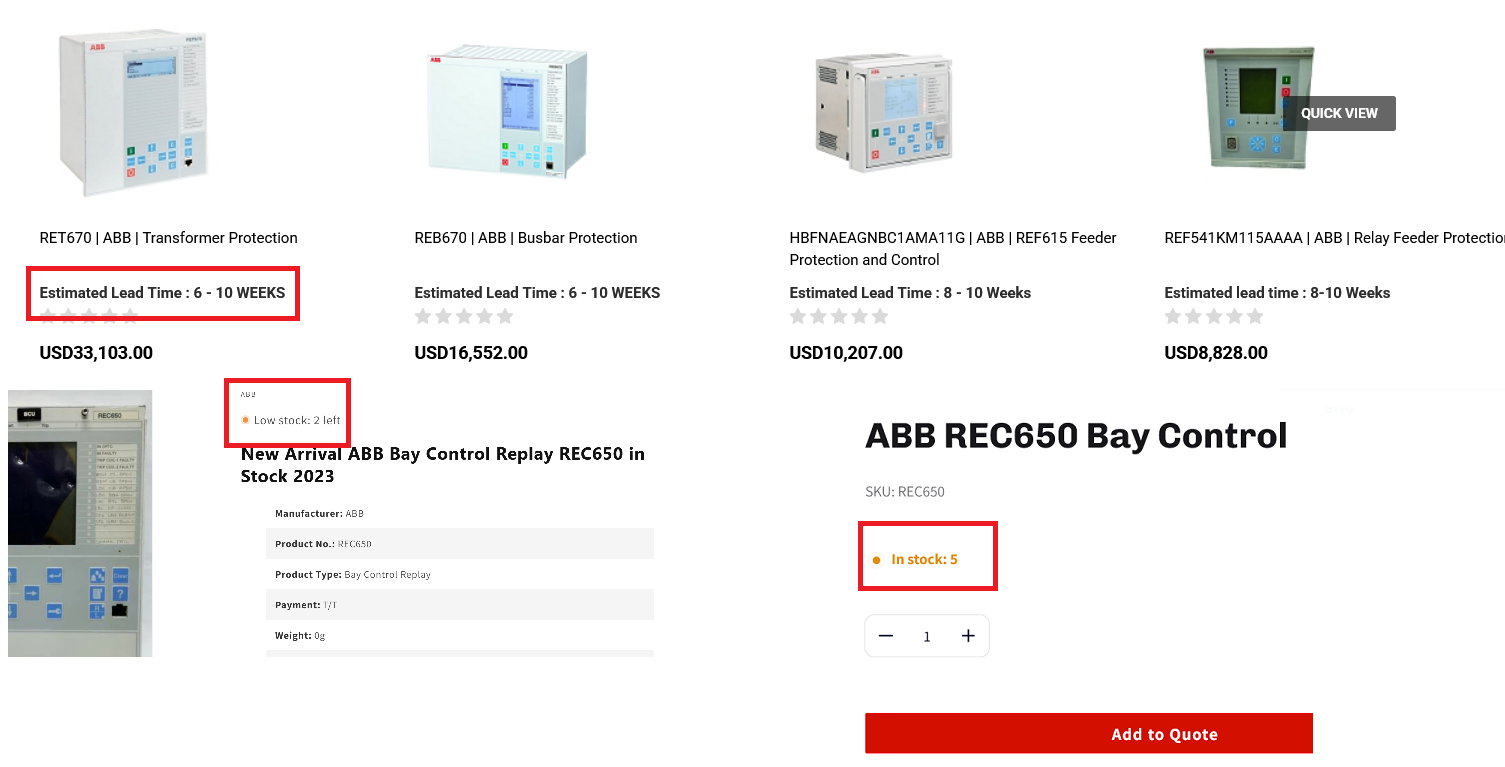

This seems to closely match the "soft-bricking" approach to CVE-2024-8036, which Midnight Blue discovered in ABB equipment during a Red Team engagement for a DSO customer. Hitachi acquired over 80% of ABB's Power Grids division in 2020, resulting in its acquisition of the Relion 650 and 670 series of IEDs, while other Relion series (such as the 611, 615, 620, and 630) remained with ABB. Architecturally, these devices all share quite a bit of their tech stack.

This vulnerability results from an Improper Handling of Exceptional Conditions (CWE-755) when an FTP operation deletes critical configuration files but does not replace them with functional new ones. Such malformed configuration updates can put the IED in an operating mode where it no longer performs its protection and control functionality and cannot communicate remotely anymore nor be reset through the Local HMI (LHMI) on the device itself.

A similar, but less potent, attempt to disrupt IEDs was made as part of the 2016 Industroyer attack against the Ukrainian electric grid. This attempt consisted of exploiting the CVE-2015-5374 Denial-of-Service (DoS) vulnerability against Siemens SIPROTEC 4 IEDs. Essentially this vulnerability used legitimate protocol commands (a trivial effort really, which now even has a Metasploit module) to put the device in firmware update mode and left it there. This disabled its protection and control functions and made remote recovery impossible, requiring powercycling the device. Interestingly enough, that particular vulnerability was over a year and a half old when deployed (similar to CVE-2024-8036) and had already been utilized half a year before the attack in a Russian Capture the Flag (CTF) competition during a conferences.

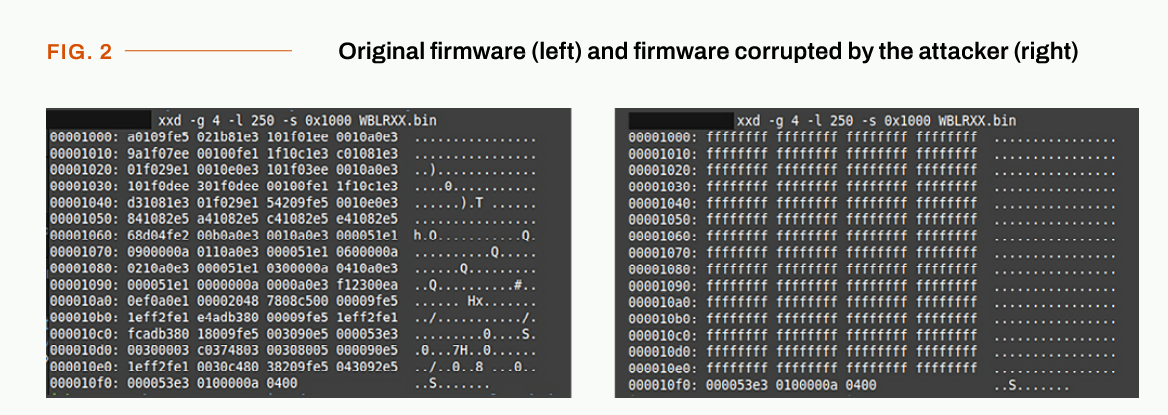

Most of the affected DER sites used Hitachi RTU560 controllers running outdated firmware versions. The attackers compromised the devices by logging in to the RTU's exposed web interfaces using default credentials, and subsequently uploading malicious firmware images in order to "hard-brick" them. While RTU560 devices come with a "secure update" feature (since v13.2.1), this is not enabled by default and suffers from a bypass vulnerability CVE‑2024‑2617 up to v13.7.7. Since none of the RTUs had this feature enabled, any malicious firmware could be uploaded.

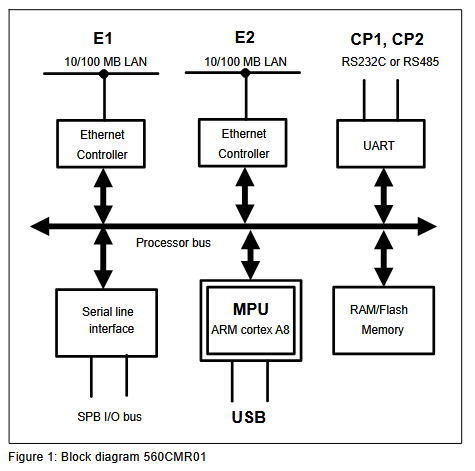

The malicious firmware had 240 bytes of 0xFF inserted at the program entry point. Based on the firmware filename (WBLRX) in the CERT-PL report, we can see this corresponded to the firmware of a 560CMR01 Communication Unit which is the central module of the RTU560.

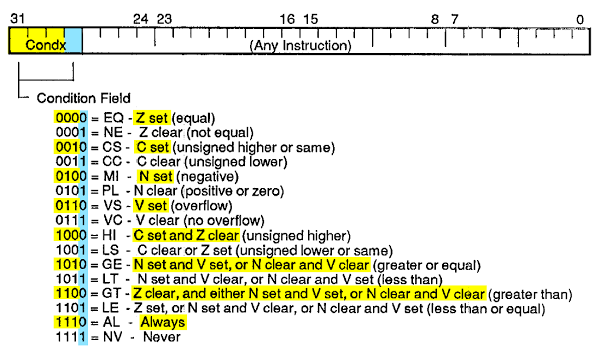

The 560CMR01 module is based around a TI AM3352 (ARM Cortex-A8) microprocessor running VxWorks and is available in two versions: R0001 with standard cybersecurity features and R0002 with a dedicated crypto chip.

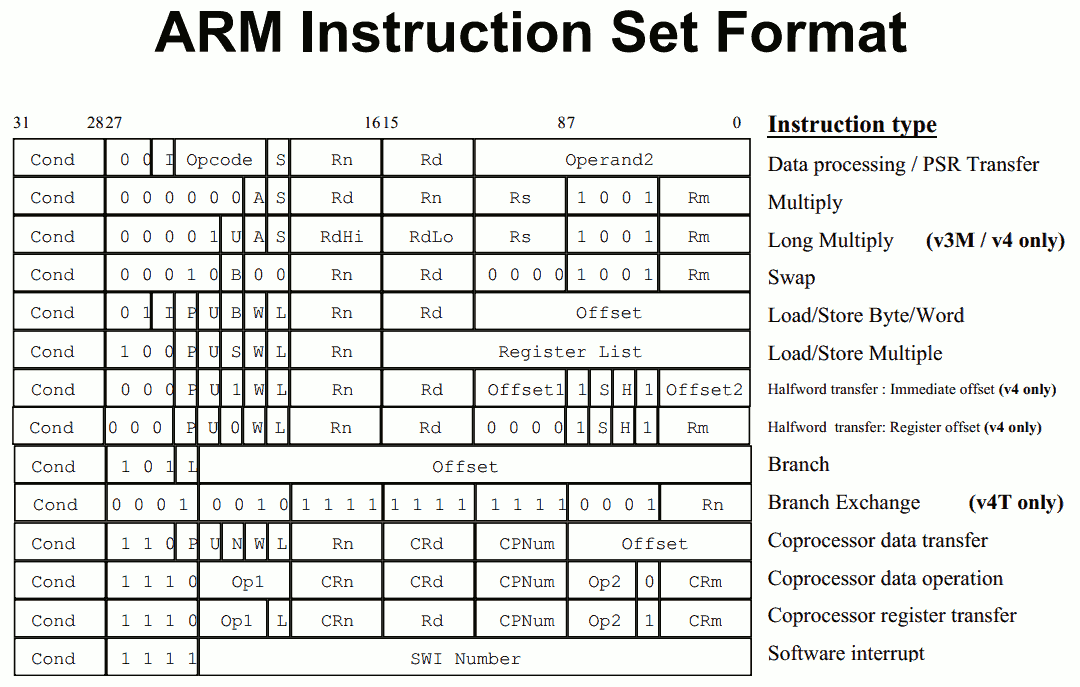

On ARM32 processors, a 32-bit instruction word of FFFFFFFF decodes a software interrupt invocation (SWI) with the maximum SWI number of 0xFFFFFF and a condition flag of 0xF indicating the instruction should never be executed. This latter conditional inherently renders it an undefined instruction which causes an Undefined Instruction exception which in most cases takes the processor to Undefined Mode and executes the Undefined Instruction handler defined in the Vector Table - apparently resulting in a device reboot (and thus an infinite bootloop) in this case rendering the device inoperable.

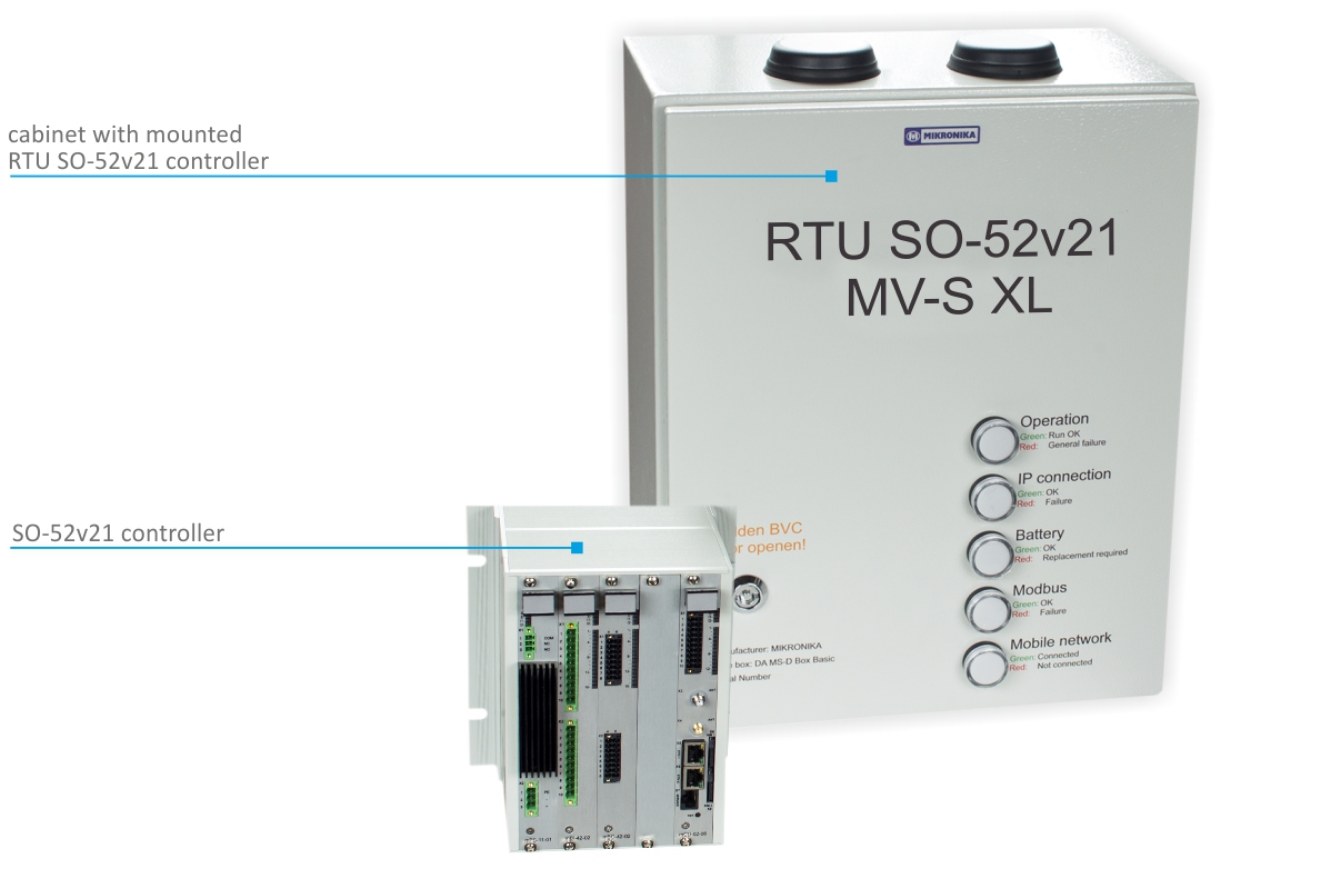

At those DER sites where Mikronika RTUs were in use, the attacker compromised them via SSH using root accounts with default credentials in order to subsequently wipe the filesystem. While the CERT-PL report does not identify the exact models of the Mikronika devices targeted, a lot of Mikronika devices are based on a Texas Instruments OMAP SoC running Linux on the ARM core which makes developing payloads fairly straightforward.

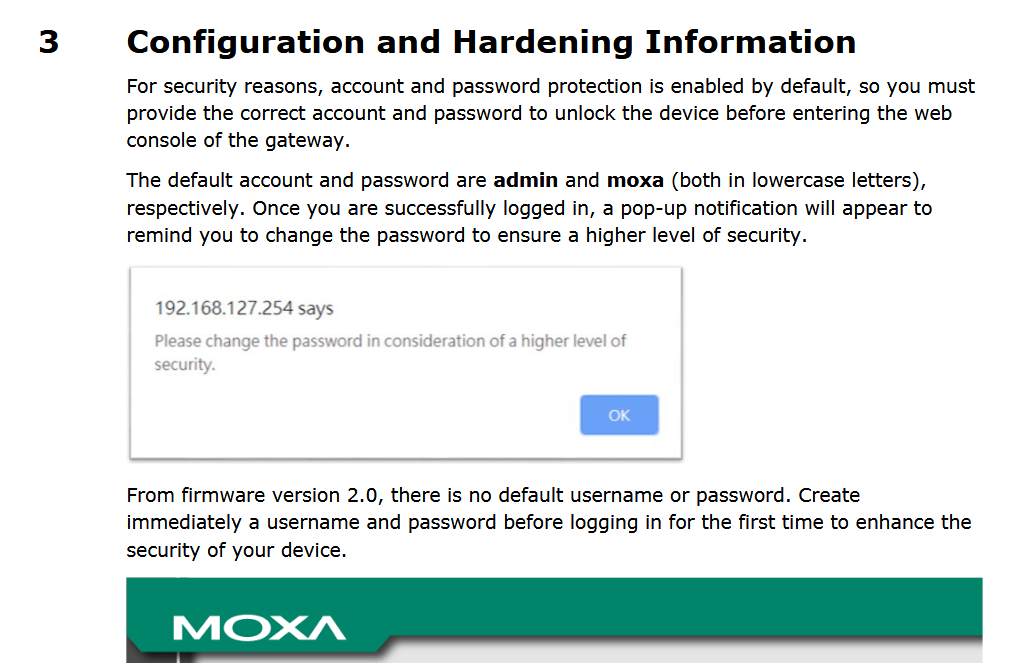

Finally, while Moxa NPort series 6xxx serial device servers operating as protocol converters where also targeted these were not bricked. The attackers chose instead to compromise them through the use of default credentials on the web interface and subsequently reset them to factory settings and change the login password and the IP to an unreachable address in order to delay operational restoration.

What's interesting here is that the attackers did not brick the devices. Instead, they merely changed configuration settings to cause operator lockout and loss of communications. This is particularly curious given that in the 2015 BlackEnergy attacks against the Ukrainian power grid, the attackers bricked a different family of Moxa serial-to-Ethernet converters in order to delay recovery operations.

In fact, Moxa serial converters are somewhat notorious in the OT security community for being riddled with various serious but trivially exploitable flaws including multiple issues around authentication and unsigned firmware in the Moxa NPort 5000 family [1,2], some of which also affected the Moxa NPort 6000 family [3]. Firmware updates for the Moxa NPort 6000 can be done through the serial console, web interface, or Moxa Device Search Utility (DSU), the latter two of which might require a username and password but given the presence of default credentials this shouldn't have been an obstacle. In his great S4x20 talk "14 Hours And An Electric Grid" Jason Larsen demonstrated pushing a malicious firmware update to Moxa 5610 serial converters in order to implant them with custom malware. No secure boot or firmware signing in sight here either and bricking is trivial compared to writing and loading an implant.

While the CERT-PL report does not state exactly what kind of NPort 6000 devices were targeted and the recently released 2nd generation (6000-G2) are reported to have secure boot and signed firmware features, it seems highly unlikely these were already used at the targeted facilities.

In fact, Moxa guidance for hardening the G2 devices explicitly states there are no default credentials on these devices while hardening guidance for the older generation devices states this is only the case starting from firmware v2.0 - suggesting that the affected facilities used the older generation devices with out-of-date firmware and bricking was likely feasible.

So why worry so much about this particular TTP? Isn't this just another flavor of the endless amount of wipers and ransomware that we've been bombarded with for over a decade now? Surely proper backup policy and a good incident response plan will prevent the worst?

To put it briefly: a bricked device cannot be recovered remotely. In many cases, it cannot even be recovered with physical access to its local interfaces. This is very different from a wiped server where in the best case scenario you have a remotely accessible Out-of-Band (OOB) management interface such as IPMI (HP iLO, Dell iDRAC) where you can simply reimage the OS and restore backups.

Embedded OT devices do not have such functionality. If their firmware is wiped or filesystem corrupted to the point that they cannot properly boot anymore, they might offer a way to restore factory default or backup firmware through an early bootloader but this will likely only be accessible from a local serial console requiring a full site walkdown and individual restoration of each affected devices. And in many cases, such functionality isn't present either or a malicious firmware update can include an equally malicious bootloader update rendering this pathway void as well. In that scenario, there really is no other solution than tearing out and physically replacing all of the bricked devices.

The impact of such a worst-case scenario is far more serious in OT too. While physically replacing a few hundred enterprise switches and servers is surely painful and costly, it is relatively straightforward and vendors and commercial warehouses will likely hold enough stock to accomodate sudden demand spikes.

For example, in the aftermath of the NotPetya wiper incident Maersk rebuilt its IT infrastructure with tens of thousands of new PCs and servers in a period of 10 days and during the infamous Shamoon wiper incident supposedly tens of thousands of hard drives were bought up around the world as quickly as possible to replaced the wiped ones. Ukrainian companies in particular have become quite resilient against such "conventional" enterprise wiper attacks constantly hitting the country.

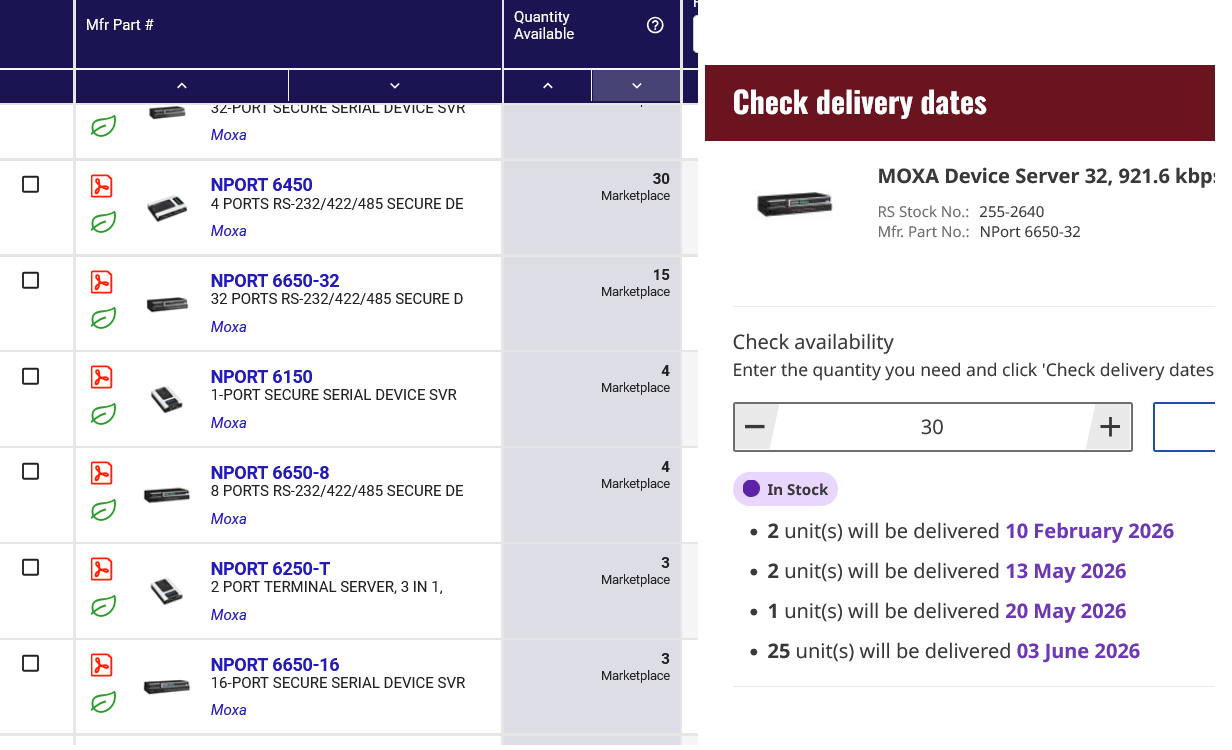

But this is not the case for embedded OT devices. Asset owners, system integrators, and resellers typically don't have hundreds of spare RTUs, IEDs, PLCs, or serial converters lying around and manufacturers typically don't keep large stock either. A quick look at online distributors such as DigiKey and RS Group as well as smaller parties shows that stock typically runs from less than ten to a few dozen at best. If you need hundred of these all at once a large portion of that will have to be backordered and possibly be manufactured on demand. In the best case scenario, you're still looking at lead times over a month. Similar worries about transformer availability in the context of threats to the electric grid were highlighted in the Strategic Transformer Reserve report to U.S. congress.

That is without accounting for the fact that replacing, commissioning, and Site Acceptance Testing (SAT) in industrial and critical infrastructure environments takes way longer than putting in new servers in an enterprise environment. And during those weeks to months, affected sites will likely not be operational. While it may be possible to overcome a prolonged loss of RTUs or serial converters by putting a remote site in local override with personnel physically present (though this rapidly becomes infeasible if too many sites are simultaneously affected), operating without IEDs or PLCs is simply impossible since they form the heart of operations and safety. This means bricking OT equipment allows attackers to scale the impact of cyber-physical attacks from hours to weeks.

First of all, bricking is not to be confused with a more conventional Denial-of-Service (DoS) utilized to amplify a possible cyber-physical impact, such as the TTPs used against the Moxa NPorts in the Polish incident or the Industroyer SIPROTEC DoS mentioned above. While complicating recovery operations, such DoS are essentially recoverable in a way that do not require full re-commissioning or physically replacing the device.

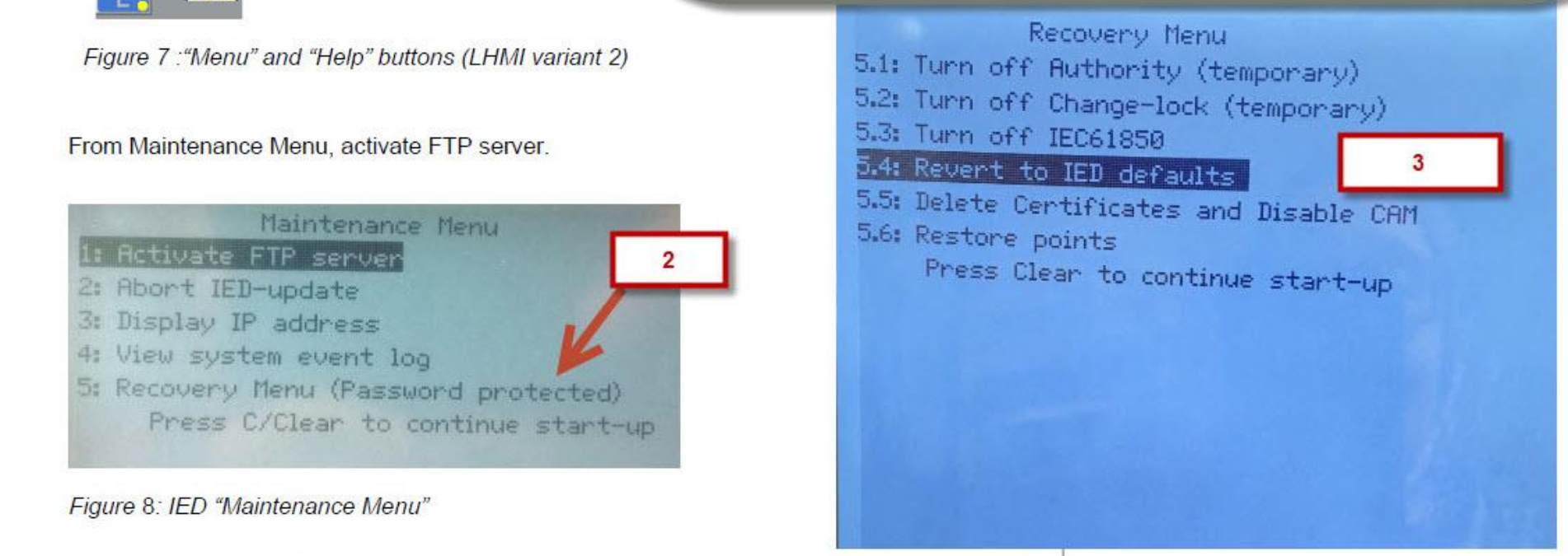

We consider "soft bricking" any TTP the impact of which is recoverable (though not remotely) through a factory reset or reprogramming from a local HMI or engineering interface, without having to resort to custom tooling or undocumented interfaces and bootloader modes.

A "hard brick", by contrast, is any TTP which renders the device inoperable in such a way that it is only recoverable by sending it physically back to the manufacturer or through great and invasive effort (e.g. undocumented debug ports, JTAG, or chip-off flash restoration).

Regardless of the degree of bricking however, it is likely asset owners would want to rip and replace any devices so deeply compromised that they can no longer ascertain full disinfection as was the case in the SALTWATER / SEASPY implants against Barracuda ESG devices.

In order to be able to brick an embedded device remotely an attacker typically first has to obtain one of the following:

In the latter two cases, the attacker will need the ability to persistently modify the filesystem (as opposed to only ramfs access) or modify flash memory. One difference between embedded systems and servers or laptops to consider is that the former typically do not use HDDs or SSDs for persistent storage but instead use either dedicated flash chips, flash memory integrated into the main SoC, or external SD/MMC cards for this purpose. We'll refer to all as "disks".

The bricking payload can then typically be implemented in one or more of the following ways:

Wiping individual files is typically achieved through:

The easiest way to wipe raw disk contents or structure metadata is through invoking dedicated external utilities (such as KillDisk on Windows or mtd-utils or flashctl on embedded systems) but these may not always be present. Native filesystem or disk encryption functionalith (such as cipher.exe on Windows) can also be abused to rapidly encrypt the disk with a key that is then thrown away - effectively wiping it.

Wipers can also implement their functionality natively. This requires first obtaining raw disk access, typically done through either:

After raw disk access has been obtained, the disk can be wiped in several ways including:

Wipers can focus on erasing general or specific disk contents but also on structural metadata such as disk partition tables (MBR, GPT). If the goal is to brick a device, it doesn't make too much sense to attempt to corrupt all files or the entire disk however. The most important attacker goal is to corrupt the minimum amount of data in the shortest amount of time in the most generic (and thus scalable) manner possible so that the device will no longer be operational and cannot be trivially recovered after a reboot. For many embedded devices, it is enough to corrupt only a few files or small part of the disk to achieve this.

Bricking a device with malicious firmware is typically not so complicated. There's a reason why so many device manuals warn that there must be no interruption of power during firmware updates. Effectively, any firmware image that will result in the device becoming non-operational and irrecoverable will do. This can be as simple as replacing early boot code with invalid instructions or an infinite loop - all the more damaging if fallback to a recoverable bootloader mode is also prevented.

For example, several ABB Relion IED series have a factory reset feature available from bootloader recovery mode through the LHMI maintenance menu:

The feasibility of an attacker rendering this recovery route inaccessible depends on the general embedded systems design. If the bootloader is updatable itself as part of a firmware update or if it is stored in flash, it could be similarly corrupted. If there is a ROM bootloader with a fallback mode accessible through physical device access (e.g. via UART console), then this may present a hard obstacle for an attacker.

One underexplored wiping TTP is the exploitation of flash memory wear. Flash memory has a finite number of program-erase (P/E) cycles which after having been exhausted render the memory non-writable and in some cases even unreliable for reading (with higher bit error counts and shorter data retention times, especially at higher temperatures). Techniques such as wear leveling and bad block management try to combat this under normal circumstances, especially for highly active flash-based media such as SSDs. One metric of SSD lifetime expectancy is "Terabytes Written (TBW)" which is influenced by underlying flash characteristics such as P/E cycles and write amplification.

An attacker could deliberately rewrite flash memory continuously in order to exhaust it. This would mean that even if a device had a ROM bootloader recovery mode or JTAG access, it simply could not restore a benign firmware image to the now destroyed flash anymore.

For embedded flash chips, the bare P/E cycle limit is typically a good indicator for how long such an exhaustion attack would take. Different NAND flash types have different cycle limits ranging between 1k and 100k and while there are some other factors (block erase time, number of blocks, etc.) influencing how quickly one would run through that most embedded flash chips can probably be exhausted in a reasonable amount of time.

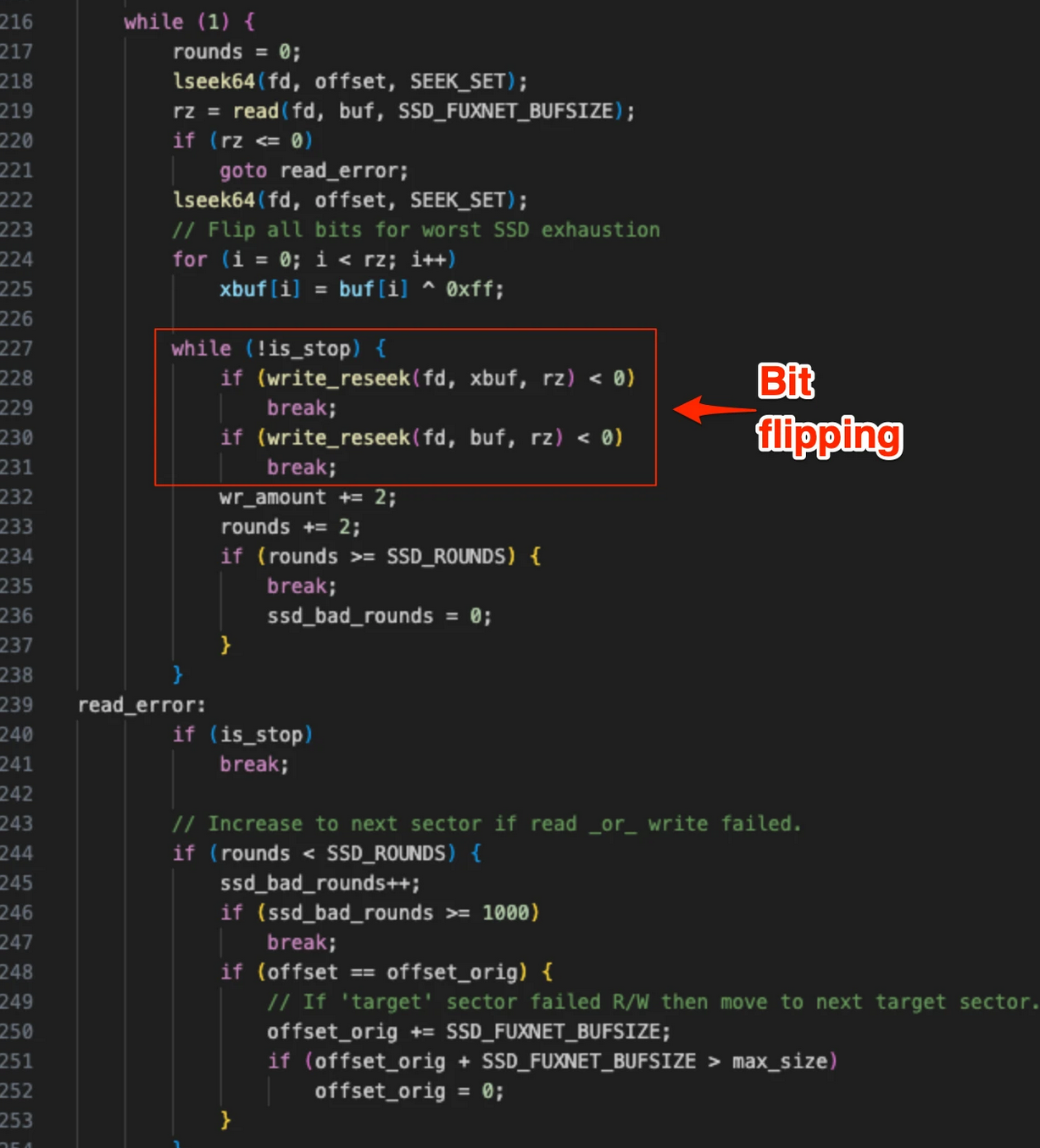

An interesting application of this TTP was observed in the FUXNET malware deployed in a 2024 attack against the Moscollector company responsible for managing sensor systems in Moscow's (waste) water infrastructure. This malware targeted various OT sensor gateways and followed up its conventional embedded wiper strategy with a flash cycle exhaustion attack. The attack approach consisted of constantly performing rewrite operations with bitflipped patterns.

In part 2 of this series, we will do a deep dive looking into how big of a problem this exactly is in the OT device landscape.

This course, aimed at asset owners, system integrators, EPC contractors, and OT equipment manufacturers will provide participants with a comprehensive and in-depth understanding of the key concepts and challenge in securing embedded systems - with a special focus on Operational Technology (OT). This training combines fundamentals and theory with real-world case studies and hands-on exercises in order to teach participants about everything from threat modeling tailored to embedded systems and the MITRE EMB3D™ framework to common embedded systems attack vectors and counter-measures.

Special attention is given to an overview of common anti-patterns encountered in embedded OT systems, by providing dozens of detailed breakdowns of vulnerabilities of different types in RTUs, PLCs, DCS controllers, routers, and protocol converters of major vendors across the tech stack ranging from bootloaders all the way to network protocols.

For those interested in advancing their OT device security assessment skills, Midnight Blue provides the training OT Device Security: Hands-on Adversary Tactics for Effective Threat Modeling and Hardening on an in-house basis.

An overview of the course can be found here.

All items